How is it that no one warned me that Bicentennial Man is the saddest movie known to mankind? I mean... I should have figured it out for myself, given that the short story was pretty sad, and the lead actor was Robin Williams, but... I underestimated the extent. Lesson learned.

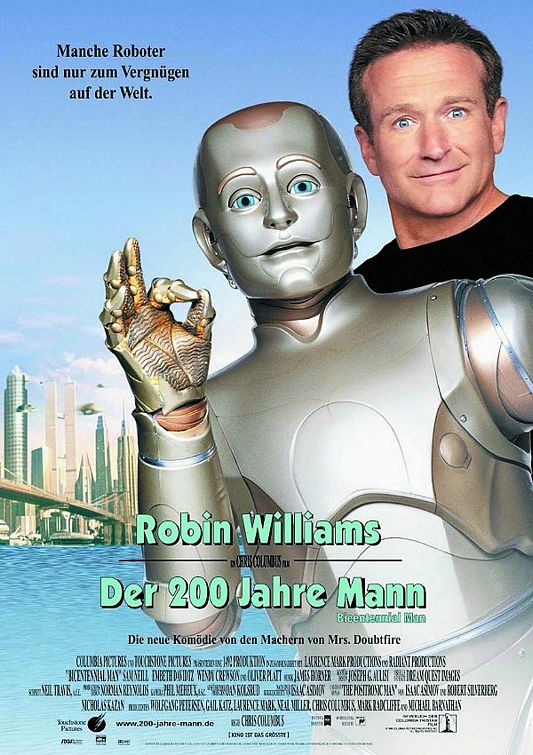

Everyone knows that movie posters are better auf Deutsch.

All right, so Plot.

Let's start with the obvious, shall we? In the short story, Andrew does not go gallivanting across the country in search of a companion. And also he does not get married, to a human, no less. That completely changes the theme, the way I see it, but I'll get into that later. The addition of Little Miss's wedding adds depth to the relationship between Andrew and Sir, as well. It shows that Sir's greatest fear is of everyone leaving him, and it justifies his later irrational anger at Andrew's desire for freedom. And in general, there is a bit more detail to the plot, because less time has to be spent on setting in a movie than in a short story, as the audience can clearly see the setting, whereas in the short story, one must rely on words. Another example of this is Andrew's creepy hovering at the dinner table when he first arrives at the family, and his getting pushed out the window, as well as his shattering of Little Miss's crystal horse; it adds dimension to the rocky start that the reader only suspects Andrew probably had.

As to point of view...

It wasn't one of those movies with a narrator built in. However, there was the addition of some subtitles saying things like "In the not so distant future...." and "Many years later...." Essentially, though, the point of view was the same. Since it was Andrew's story, we rarely if ever saw a scene without him as the central character. Therefore, the point of view was third-person omniscient. I also think it was slightly less limited than the short story could have been argued to be because it lacked the biased interludes of prose. We see Andrew's reactions, but we get no concrete words to describe them, so they are left open to interpretation, as are the reactions of all the other characters.

A lot of the plot differences contributed to the differences in characterization, as well.

For instance, when Little Miss gives him her stuffed animal named Woofy in return for the wooden horse figurine, it strengthens their bond as characters. It also makes the last moments of Little Miss' life much more *cringe* tender, because she was holding the little old horse figurine in her wrinkled, nearly-dead hands. It also tenderizes (seewhatIdidthere?) the moment when Andrew takes in the stray puppy, and later we find out he's named it Woofy after the stuffed animal Little Miss gave him. These are examples of indirect characterization, but direct characterization isn't something one sees in movies a lot. Speaking of referring to oneself as one, Andrew does that a lot in this film, but he stops when he is freed by Sir. This strengthens the development of both characters because it shows both Andrew's value for freedom and Sir's care-in-spite-of-anger/hurt/bitterness when he notices the change. And I loved how in the movie, Andrew is afraid of heights because of when the mean other Miss makes him jump out the window. Also, when Andrew runs off looking for other robots like him, it makes his character more sympathetic, as the audience begins to see the loneliness of his condition. Also also, it reminded me of this:

As for setting...

They are extremely similar. In both, the story begins in the somewhat foreseeable future--2005 in the movie, which is now the past-- and continues for exactly two hundred years into the future after that--ending in 2205, which is well beyond my estimated longevity. In both, the story takes place in some ambiguous portion of the United States of America. When Andrew goes about trying to find himself a friend, I have no idea where all he looked, and he might well have left the country a time or two, but there's no telling for certain, and it's not really important to the story. I don't believe the short story mentioned the Martins' living near the ocean. That adds to the romantic and sentimental element of the story, I suppose, although it seems annoyingly cliché. It does make sense for Andrew's woodcarving hobby to have begun thusly, however.

And at last... theme.

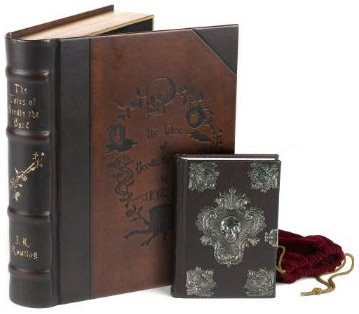

In the short story, the theme was more about the foolishness of bigotry and the values of freedom. In the movie adaptation, the theme was more about the importance of love and companionship to the human condition, and how time inevitably changes all that and leaves people brokenhearted until they die too, perpetuating the cycle. Ahem. I don't like when movies try to make that seem okay. In analyzing how this happened, I'm going to first point out the addition of the piano scenes with Andrew and Little Miss. It would seem that piano scenes conveying sentimentality are a pop cultural favorite in film adaptations. Check out this blatantly illegal recording someone did of the latest Harry Potter to see what I mean:

Also, Sir starts us on this path early with his "lessons" to teach Andrew what he hasn't been programmed to know, one or two of which included The Birds and the Bees, for sure. Also also, he... you know... marries Portia and dies holding her hand.

HEY. They made it look like he didn't even ever know that he was declared a man! Whaaat's theee deeaaal wiiiith thaaaaaat??? I suppose they were trying to make some kind of point. It doesn't matter what other people think. What matters is what you know in your heart. Blaaaah blaaah blaaaah it STILL would have made Andrew happy. Instead, he just died.

I'm going to assume the girl android with the dancing-->temper-->skin was just incorrect. I know she's a robot and all, but... Andrew knew. Otherwise, Christmas is canceled.